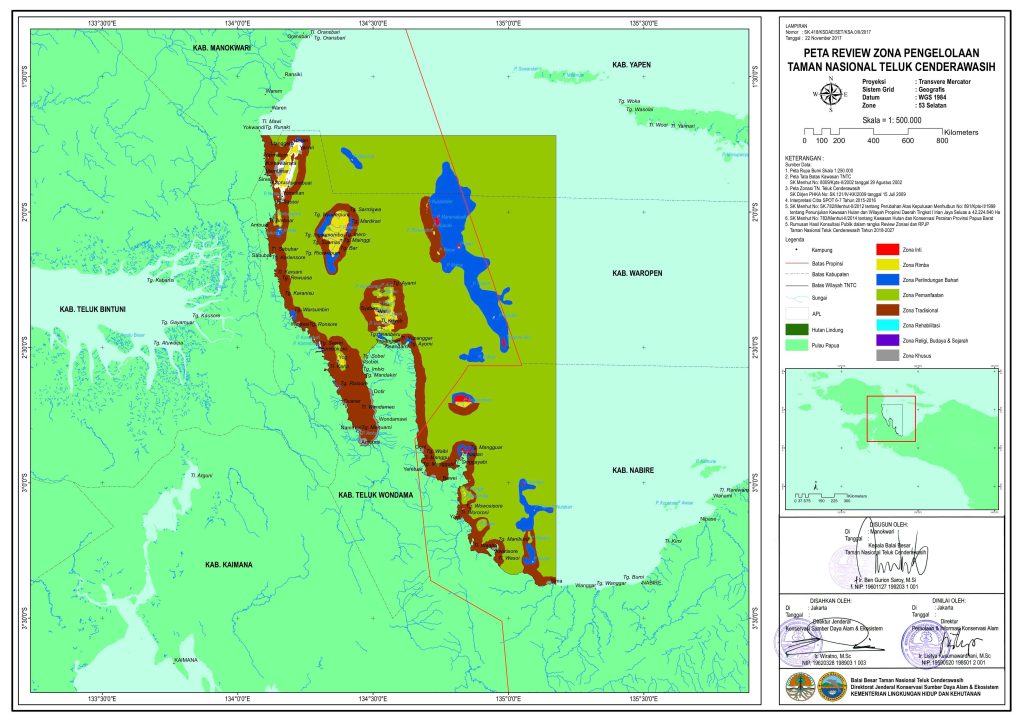

Zoning Map

The park includes coral reefs, mangroves, coastal habitats, and tropical forest. Its ekosistem laut support around 200 coral species and at least 836 species of fish, including more than 15 endemic reef fish such as the Cenderawasih fairy wrasse (Cirrhilabrus cenderawasih). Whale sharks are a highlight, with at least 126 individuals identified—making the park popular for ecotourism and research. Other marine life includes seven species of sea turtle, dugongs, dolphins, crocodiles, and mollusks such as giant clams. The mangrove forests along the park’s eastern edge provide important nursery grounds for young fish and help support the region’s overall ecological diversity.

Local communities are central to the management and conservation of Teluk Cenderawasih National Park. Many villages lie within or near the park, including in Teluk Wondama Regency, where more than 41,000 people depend on marine resources for their livelihoods. Park management actively involves local communities, district governments, and organizations like WWF-Indonesia.

Indigenous Papuan communities hold strong customary systems (adat) that govern territorial rights and the sustainable use of natural resources. One example is sasi—a traditional practice of temporarily closing certain fishing areas or banning the harvest of specific species to allow ecosystems to recover. Practiced in places like the Auri Islands, Menarbu Village, and Sombokoro Village, sasi acts as a rotating no-take system and has shown promising results for reef health and fish abundance. Revenue-sharing from park entrance fees and support for local products further strengthen the connection between conservation and community wellbeing.